What lengths would you go to in pursuit of untouched powder skiing?

Would you pay to schlep along a muddy road for hours and sleep in a plywood-walled shack, huddled against the cold winter night inside a sleeping bag you had to bring yourself?

Would you lift off in a small helicopter to ski in a largely untested manner?

That’s exactly what CMH Heli-Skiing’s 18 earliest guests did in April 1965 when they joined the very first weeks of paid, guided backcountry helicopter skiing to succeed in North America.

The groundbreaking excursion was organized and led by the late Hans Gmoser, renowned Mountain Guide and founder of CMH Heli-Skiing and the sport.

Although Hans had been involved in earlier attempts at using a helicopter to transport skiers, none had truly succeeded at scale until April 5, 1965, when, between the granite Bugaboo Spires in the remote mountains of British Columbia, heli-skiing officially took off.

Stirring up interest

The idea for the April 1965 trip was years in the making, but it was finally cemented in Hans’ mind during a ski touring week he led in the Bugaboos during the previous spring in 1964.

Having already hiked and climbed the area during the summertime, its potential as the place to finally pull off heli-skiing was further solidified when he first experienced it blanketed in snow.

Buoyed with confidence by the unmatched quality of skiing, Hans began planning two weeks for the following 1965 spring.

The first week was open to anyone interested who was a good fit to join the adventure.

The second week was reserved for a ski touring client, American alpine ski racer Brooks Dodge, who for a few years had been trying to arrange a trip with Hans that included touring, plus a few days of helicopter lifts.

One week of skiing at old-school prices

The search for week one guests began with an advertisement Hans included in the 1964/65 edition of an annual brochure he printed to showcase upcoming guided ski touring opportunities.

In small print, it read:

For the first time we are organizing ski touring weeks where we use helicopters for the uphill transportation in Canada’s most spectacular ski country. Depending on the number of participants each person will get anywhere from 7 to 12 trips on the helicopter during this week. Each trip will enable them to make a 3 to 5 mile downhill run. On days when the weather does not permit flying regular ski tours will be arranged. All inclusive cost, party of 15 $203 each, party of 10 $266 each.

Hans spread the word to his network. By the following spring, he’d found enough enthusiastic guests and had organized a small but talented support team of equally adventurous souls.

Jim Davies, a young mountain pilot from Banff, would fly the helicopter; mountaineer Franz Dopf, Hans’ friend since childhood in Linz, Austria, would manage the base camp and help with the skiing; and Emily Flender, from Cambridge, Massachusetts, would cook.

On April 4, 1965, the first week of heli-skiing began with six of Hans’ longtime ski-touring clients as guests: Dieter von Hennig, Erling Lunde, Lloyd Nixon, Bob Sutherland, Ed Sutton and Inga Thompson.

Day one was spent transporting everyone to a vacant lumber camp near the foot of the Bugaboo Spires, where they would sleep, eat, and fly from each morning.

But before any skiing could begin, they had to get to camp. As it turned out, this was a more harrowing journey than any of the guests imagined.

A winding road

Today, guests of CMH Bugaboos take a 10-minute helicopter flight from the bottom of the nearby Columbia Valley to the lodge. But, to keep trip costs low, this leg of the journey was originally driven by road using a combination of cars, trucks, and snowmobiles.

The vehicle convoy for the first trip began in Banff, AB, and drove to the small but well-stocked Brisco General Store (still in service today) in the quaint roadside community of Brisco, BC. Here, the convoy made one last pit stop before leaving the paved highway and turning onto a dirt logging road that climbed towards the Bugaboos. The vehicles had to drive slowly along the bumpy, 45 km (28 mi) road, which was even more rugged under April’s springtime conditions. It was muddy at lower elevations and still snow-covered up high.

“Hans met us in Banff, from whence we drove in various cars to the logging road that accessed the Bugaboos,” guest Dieter von Henning once described. When the group reached an elevation near the snowline where the already sodden road deteriorated further, they transferred to a waiting machine.

“We then switched to the Nodwell, a tracked all-terrain vehicle, which better negotiated the muddy road,” he continued. “I recall passing a trapper’s cabin where we saw beaver skins hanging out to dry.”

Weather added further complications during the second week when rainy conditions down low turned the road nearly impassable.

“With Brookie Dodge’s first group that trip took from 5:00 in the afternoon until 2:00 the next morning,” Hans recalled of the nine-hour debacle. “Numerous times we were stuck in the mud, got rained upon and pushed the vehicles for a good part of the way. It wasn’t too long before one of those early guests took me aside and said, ‘Why don’t you charge another $30 and fly us in and out?’ It seemed a terrible waste of money to me but if our guests were prepared to pay, it would make everyone’s life much easier. It also made our offering more appealing and increased the demand.”

Bare-bones basecamp

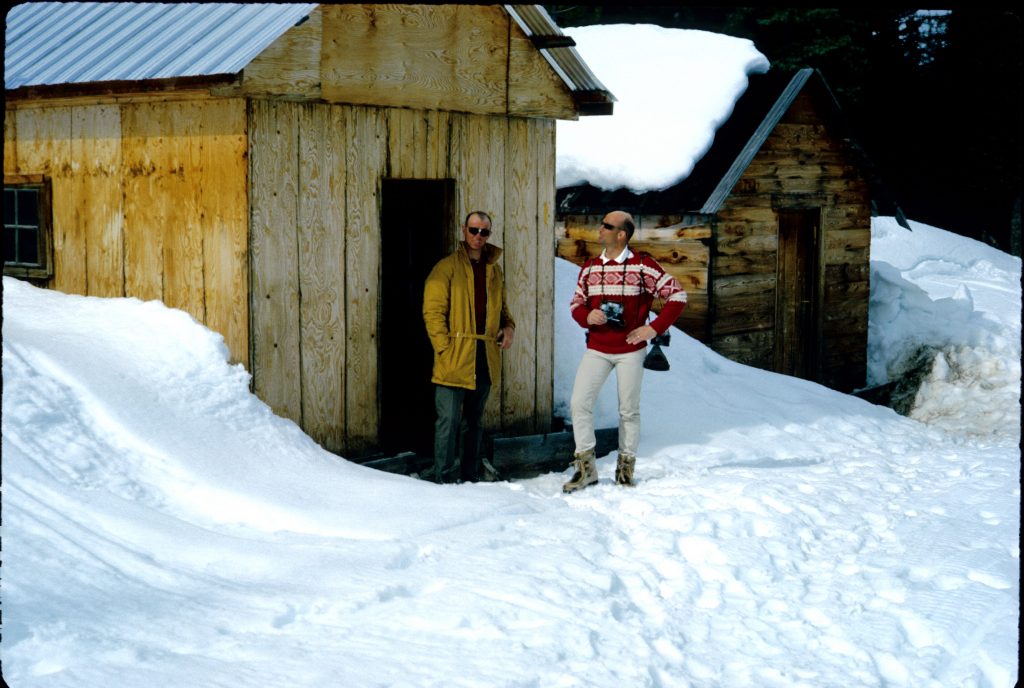

After hours spent jostling up the road, the first guests reached their home for the next week: a used logging sawmill site owned by Stone & Gillis.

It was located beside a fork of the Bugaboo River at 1,524 m (5,000 ft). A collection of small bunkhouses and a large cookhouse sat in a logged clearing, backdropped by the rounded silhouette of Houndstooth Spire.

The cookhouse was a gathering place for everyone to eat and lounge. It was also where Hans, Jim, Franz and Emily slept.

The uninsulated plywood bunkhouses each housed 2-3 people and were reserved for the guests–-much to their disbelief upon first sight.

“Hans pointed to one and said Lloyd Nixon and I should take that one,” Dieter recalled. “I could barely open the door, as the cabin was full of snow. First I thought it was a joke. But we were assigned another, or the snow was shovelled out, according to Lloyd. Hans would wake us in the morning by coming in the cabin to light a fire in the small wood-burning stove. We slept on iron bedsteads in our own sleeping bags.”

Soon, though, the rustic living arrangements didn’t matter.

The creaky, cold bunks faded into mere footnotes the following day when the guests skied their first run down untracked powder and realized the helicopter unlocked an entirely new world.

The reward

The plan for this trip was to use the helicopter stationed at the lumber camp if the weather was good for flying. If not, they would ski tour as they’d always done, using skins to climb. All the earliest guests were established ski tourers, so using the helicopter to move around was an extension of what they already knew.

April 5, 1965, dawned clear and bright: ideal flying conditions.

While the guests finished breakfast in the cookhouse, pilot Jim Davies warmed up the helicopter. It was a Bell 47G-1 ‘bubble copter,’ nicknamed for its bulbous plexiglass front dome. The small, slow-climbing machine had a single, centre-mounted pilot’s seat in the front and a two-person passenger bench seat in the cockpit’s rear.

Hans and one guest climbed in behind Jim. The machine whirred to full power, and they lifted off, flying high onto Bugaboo Glacier. Jim dropped the pair off and returned to ferry the rest of the group. Moving just two people at a time was slow going. Those who’d been dropped off waited in place for around 40-50 minutes before the full group was eventually assembled.

Standing atop the valley and looking out at what was before them, the group was thrilled by the novelty; it was still early in the morning, but they were already at an elevation that would normally take a full day to achieve ski touring.

All that remained was to descend.

They pushed off and enjoyed a legendary run, following Hans’ yodel down the glacier to the valley below.

The group spent the next few days repeating the same procedure and exploring different runs, returning to the camp each evening to relive the day over warm food prepared by Emily.

In his brochure for the following 1966 season, Hans described some of the skiing from those first two weeks:

One day stands out particularly in my mind. Fresh snow had fallen during the night and when at 7 a.m. we took off on the first flight the mountains looked unbelievably beautiful. There wasn’t a mark on the snow anywhere. In 10 minutes we were 9,000 feet high on the shoulder of North Post Spire. From here we skied 4,000 vertical feet down the tongue of the Vowell Glacier. It was a run none of us will ever forget. A steep, perfect bowl with not a single track on it. At the bottom the helicopter waited and flew us to the top of 11,000 foot Mt. Conrad. There was hardly enough room to land and all around was a sea of glaciers and mountains. One of these glaciers on the north side led 10 miles into the valley. The light and snow were perfect. Your shadow was outlined clearly in the snow ahead of you and you could watch yourself ski while you skied. We were in ecstasy and one of the guides remarked, “The only worry I have today is that somebody might go crazy!” After this the helicopter took us back to a 10,000 foot saddle behind Pigeon Spire and from here we skied down to the lumber camp on Bugaboo Creek where we stayed.

Week two gets underway

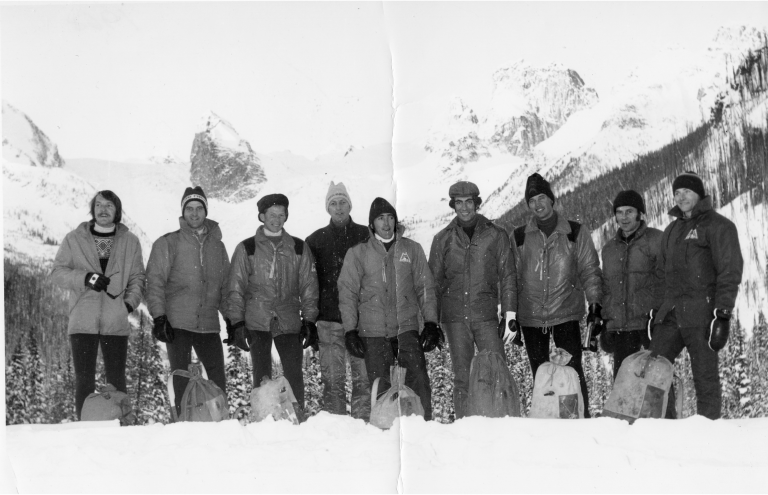

With a successful initial week complete, Hans bid farewell to the first guests and welcomed Brooks Dodge’s and his 11 companions, who hailed from ski clubs in the U.S. They were Judy Allen, Ken and Tom Boll, Roger Cameron, Carl Dahl, Brooks and Ann Dodge, Charlie Gibson, Bill Nichols, Jan Phillip, Munro Proctor and Jim Schenck.

Hans explained how it worked with up to 16 guests:

While everybody eats breakfast the pilot warms up the helicopter and as soon as this is done the first two are lifted to the top of their run. In short order the other[s] are brought up and then this party will begin to ski down. In the meantime group number two is flown up. When this is done the first group is already waiting in another valley to fly to the top of their next run and during that time group number two follows their ski tracks on the first run. In this manner we make anywhere from two to four runs, by which time it is 1 or 2 pm. We all now return to the lumber camp and rest for tomorrow’s skiing.

This is the same general leap-frog pattern still used at CMH today, even though helicopter capacities and group/guest numbers have since grown.

A match lit

Despite a few hiccups, the first heli-skiing trips wrapped up as resounding successes.

“What they experienced was enough to have them extol the beauty and thrills of heli-skiing to such an extent that 70 skiers came in 1966 and 150 in 1967,” Hans later wrote.

Like the thousands of other skiers and riders yet to come, heli-skiing’s first participants were swept up in the size and beauty of the landscape, awed by the amount of snow-socked terrain the helicopter and guides freed them to ski.

Whether those first hardy participants would’ve gone for it if they’d known all the exact details beforehand is a question that thankfully never needed to be answered. The skiing they enjoyed outweighed any discomforts and there was no looking back.

Comments

I love to see this story and the photos. My father, Evan Bullock, owned Bullock Helicopters in Calgary who Jim worked for. Bullock Helicopters was the operating helicopter company for CMH for several years and my dad’s general manager Eddie Aman was the GM for CMH to build the Bugaboo Lodge. Eddie shared some great photos with me he took during the construction. It was such a time of pioneers, innovation and a great deal of bravery for many. Thank you for the story. This was truly the beginning of this industry and Hans was a true pioneer!

Penny, thank you for reaching out with this comment. What a fantastic connection! Bullock Helicopters is mentioned in another story about helicopter technology that will be published on Thursday this week, so be sure to watch for that. It includes a passage from Hans Gmoser, who spoke highly of the support Bullock provided. If you have any of the photographs you mentioned and would like to share them, we’d love to see them. You could email them to stories@cmhheli.com.

I enjoyed this post very much. I have been skiing with CMH since 1984, although not every year. I have my reservation for five days in Revelstoke this April. I have had a lifetime of positive, life affirming experiences in the mountains with CMH, and I recommend it to all of my skiing friends. I had the great good fortune to ski on multiple occasions with Hans, and several of the other people mentioned in this article. It’s sad that Hans is no longer with us, but his spirit is in those mountains, and in the lodges, and most of all, in the staff, guides and management that make these experiences possible for the rest of the world.

Great story, Kelsey! I’d heard many pieces of that story over the years, but never in one place like that .. and in such a fun and compelling way. Thank you!

Great article – so fun to read about the early days (and to feel quite a bit of jealousy that I didn’t come along until much later in the CMH history). Especially cool to hear about places like Pigeon Spire’s role in the early days and think about how they are still core to the experience at the Bugs. Can’t wait to read the rest of the installments (and to come skiing with CMH this year).

WONDERFUL STORY. My father and I followed it from 1965 on!

Good job.

I was ever thrilled with our trips and the whole operation

In the beginning it was a perfect getaway from everyday life

No electronics. Just the wilderness no phones meet people

I’m 83 but have logged over 4 million .love the stall. And the operation my 2 sons love it also

Logging over 4 million is no joke! Thank you so much for sharing, Ralph. We’re honoured to hear how much the trips have meant to you over the years. Those moments you describe are exactly what we hope everyone can experience. It’s awesome that your sons love it too.

Good job.

I was ever thrilled with our trips and the whole operation

Loved the staff not stall

My only disappointment was my week in February (short days}

I was the only one even close to 200 thousand v. feet but Friday is chicken wing night so stopped early. I was 800 ft short but still had Saturday morning. Well couldn’t fly.

I would have been the only one on the wall.

I’m over a million ft at galena so I’m dam lucky guy.

I was there before the lodge and after.