It’s easy to underestimate the level of experimentation that occurred during the earliest years of heli-skiing.

In today’s modern world, the helicopters we fly in and the radios we communicate with are familiar, well-practiced tools we’ve seamlessly integrated into our world in the wilderness. They’ve become de facto elements of a great day chasing turns.

Yet, that wasn’t always the case.

Particularly during the first five years of commercial heli-skiing’s 1965 start in North America, CMH Heli-Skiing’s earliest guides, pilots, guests and staff were innovating not only with a new way of taking people skiing but also with some of the big-bucket technologies that enabled the burgeoning sport’s development.

They did so with an initial understanding of some technologies that CMH founder Hans Gmoser bluntly described as ‘nil.’

Accessing remote terrain and deep pockets of incredible snow was the motivation and primary focus, yet to do so required simultaneous experimentation with helicopters, radios and repeaters, guiding procedures, safety practices, ski equipment, snowmobiles, and more.

Figuring those out was the key to unlocking the reward: untouched powder in faraway places.

Discovery and testing

Flying was the biggest unknown. Helicopters were still quite new to the aviation world and hadn’t yet been used for this application at scale. Testing helis as high-tech ski lifts for paying guests came with a steep learning curve, many brazen ‘let’s just see what happens’ moments, and occasional near misses or even tragedies.

Learning how to coordinate the hour-to-hour and day-to-day movements of a heli-skiing program was another challenge because, for the first four years of heli-skiing, there were no radios to communicate between the guides, the pilots, or basecamp. Nor were there telephones to call between the areas’ basecamps or lodges and the nearest towns, which could take hours to reach by snowmobile.

Then there was the logistical puzzle of how to transport skis, poles, guests and guides safely and efficiently using a helicopter that climbed slowly and only held a few passengers at a time.

All of this—plus snow safety, terrain knowledge, landing procedures, and much more—had to be realized in real-time alongside the earliest years of guests, at a level that hadn’t been tried before.

Since everything is new, all our ideas have to be put to the test.

Hans Gmoser

Looking at it in the rear-view mirror, the degree of risk-taking, hard work, and sheer willingness to try that the first guides, pilots, guests, and staff committed to is something to marvel at today.

“Since everything is new, all our ideas have to be put to test,” Hans wrote in a report to the Government of British Columbia during the early 1970s. “A good deal of information we have gathered during the last seven years has been brought into focus only through trial and error.”

In the report, Hans outlined that the still-infant heli-skiing industry would only succeed if the government allowed it enough time to work through elements that needed to be honed.

“All this potential,” he wrote, “cannot be realized if at this critical stage in development, the new industry is not given a sheltered period to overcome the initial growing pains.”

Luckily, the government was a cooperative partner and worked with the earliest heli-skiing operators to shape how and where the industry developed.

A shared pursuit

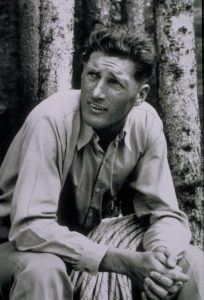

Hans, a passionate and sometimes relentless leader, forged the way alongside CMH’s first pilot, Jim Davies, and the earliest guides, guests, and staff.

A key partner to Hans was his lifelong friend and fellow Mountain Guide, Leo Grillmair, who immigrated with Hans from Austria to Canada. Leo helped found CMH and invested as a business partner, but was not often in the spotlight. At first, Hans focused on developing heli-skiing while Leo managed the ski touring trips that initially kicked off their entrepreneurial journey. When heli-skiing eventually became so popular that it needed more support, Leo became the lead guide and Area Manager for CMH Bugaboos, where he stayed for 22 years.

Everyone involved worked their way through untangling the on-snow and in-air logistics, and coordinating a growing number of staff.

There was also the paperwork, finances and business development required to facilitate the fun days on snow. Everything grew in scale as the popularity of heli-skiing took off.

In short, it was a monumental effort.

Hans frequently emphasized that it was by no means he alone who should be credited for the invention of heli-skiing and its success, for there were many others who took huge risks, experimented, and worked at a tireless pace to give the sport its start.

This included early guests, fellow guides, pilots, office staff, family, cooks, hospitality staff, maintenance crew, mechanics, investors, architects, builders, community partners, and more—the list is long and deep.

As CMH developed, particular years of rapid expansion or tumultuous financial times were stabilized by fierce guest loyalty—there were even some guests who contributed significant sums to keep heli-skiing alive.

Hans was always acutely aware of this aspect.

“The strongest driving force behind our rapid expansion was the tremendous amount of support and loyalty our guests bestowed upon us,” he once wrote in reflection.

“From the outset, I was amazed at how regularly how many of our guests returned year after year. Before long some of our guests came twice a year, then three times, then four times. They kept bringing their friends, organized groups to fill up whole weeks and actually worked hard to keep all of our places full.”

Business matters

Together, everyone involved in heli-skiing’s birth and the development of CMH figured out, piece by piece, how to run an extremely complex business—all with the complicated logistics of operating remote bases. They grew it over decades into a multi-layered hybrid that is simultaneously a guiding enterprise, a helicopter company, a travel booking agency, a world-class hospitality service, a transportation hub, a mapping, forestry and wildlife stakeholder, a gear supplier, a mountain rescue and avalanche forecasting service, and more.

It’s possible that none of it may have been if that first group of heli-skiers hadn’t thrown caution to the wind and lifted into the air.

What follows is a story pulled from a history of CMH Hans wrote years ago for CMH’s 25th anniversary. His retelling of a scenario that’s now nearly impossible to fathom illuminates just a sliver of what it took to blaze a trail in the snow-filled mountains of British Columbia so heli-skiing could get its start.

In Hans Gmoser’s words

Editor’s note: To reflect and preserve the late Hans Gmoser’s voice, the writing below has not been modified or edited. Grammar, capitalization, and punctuation remain true to the original. The subheadings and minor clarifying notes [in square brackets] are the only additions that have been made.

Misadventure in the Bugaboos: a cold night out

The first four years we operated without any radio communication. In 1969 we began to experiment with a high frequency single side band radio at Bugaboo Lodge and started using FM radios between the guides, the helicopter and the lodge. The FM radios had limited range and only worked “line-of-sight.”

In those days, one simply assumed that everyone else would always make the right decision and do whatever was possible in any given circumstance.

One also took certain precautions. For example, if we were skiing in areas where the runs did not lead back into Bugaboo Creek, we always took our climbing skis along. Should the helicopter fail to return, the reasoning went, we could always climb to the top of a ridge and then ski home.

In early February, 1968, we were skiing in the Vowell Group. Shortly after 10:00 a.m. the helicopter went to the lodge to refuel. At 2:00 p.m., we were still waiting for his return. At that point, we decided we should climb to the top of the Black Forest to get home before nightfall. Most of our guests had never used climbing skins and it became obvious, within half an hour, that this was going to be an ordeal. Kiwi [Lloyd ‘Kiwi’ Gallagher, guide] was breaking trail, while Leo [Leo Grillmair, guide and CMH co-founder] and I stayed behind, helping the stragglers. At 4:00 p.m., not having covered much ground, I heard the noise of a Bell B1 helicopter coming up the Vowell Valley. I immediately asked everyone to turn around, raced to the valley myself and got there just as the helicopter landed. It was [pilot] Derek Ellis from Golden.

When [our original pilot] Jim Davies had returned to the lodge that morning to refuel, the engineer grounded the machine because there were metal shavings in the transmission. Jim then drove to Brisco on a Ski-Doo [a multi-hour drive] and phoned Derek, who responded immediately.

We were 36 people. Derek could only take two at a time and each round-trip took 12 minutes. At best, he could get half of us to the lodge; the others spent the night out. Derek told me that there were two cabins eight miles down the valley. I asked Leo to start immediately with most of the men towards the cabins. Kiwi and I stayed behind to load the others into the helicopter.

On each return trip Derek brought food, drink and blankets. Before he made his last trip back to the lodge, we loaded all the food, blankets, plus Kiwi and Stu Wilson (one of our guests) into the helicopter. Derek was to take them to the two cabins. Kiwi was then to break trail from the cabin up the valley and eventually meet Leo and his group. I even gave them my pack, my jacket and warm-up pants, as I intended to make very fast tracks, now that I was alone and a trail had already been broken.

It took a long time for Derek to return from the two cabins and I became suspicious. When he finally did return he just said, “Boy, those cabins are a long way down!” By now the die was cast! Almost dark, there was just enough time to load the last two guests on the chopper before Derek left for Bugaboo Lodge.

The cold was beginning to bite through my sweater but I knew it wouldn’t take long to generate enough heat to keep warm.

Hans Gmoser

It was a clear, cold night as I swiftly glided in the track Leo and his group had made across the open flats along Vowell Creek. The cold was beginning to bite through my sweater but I knew it wouldn’t take long to generate enough heat to keep warm. Besides, it should take me, at most, two hours to reach those cabins. With any luck, Leo would already be there with his group. They would have a fire going, there would be plenty of food – it should be a pleasant night after all.

Lost in these thoughts, I suddenly caught up with two of our people who were at the tail end of Leo’s group. I had barely gone two miles and these guys had left two hours ahead of me! They were already tired and had blisters on their feet. Half an hour later, we came upon all of Leo’s group, stumbling in the dark along Vowell Creek. The chance of spending the night in the two cabins became ever more remote. Soon, there was no sense in continuing. We stopped and made a big fire with the abundant wood. By 5:00 a.m., the first inkling of daylight, we had enough of this and continued our walk.

Around 7:00 a.m. the river flattened out and we came into a clearing. That same moment we heard the helicopter land nearby…and spotted the two cabins.

The helicopter delivered a wonderful breakfast including boiled eggs, bacon and fresh pastries. The sun came out and everything was suddenly very pleasant while we waited our turn to be flown back to the lodge.

Such situations impressed upon us time and time again that, in spite of our “high-tech” lift, we were still dealing with raw, uncontrolled nature.

Comments

My parents, Dawn and Bill Hazelett, were longtime CMH friends and skiers. They had many stories but reading about “experimenting” with helicopters reminded me of this one. As I recall the group was in a Sikorsky helicopter. They were all standing holding their skis. The chopper started to spin out of control and Hans yelled, “Get up front!” They did and the helicopter righted. I guess the experiment with the Sikorsky was short-lived.